By Keith Walsh

Author Tosh Berman, son of artist Wallace Berman, grew up in the 60s, in small home spaces around Los Angeles that also served as art studios where his father’s art was created. “Basically, you know, I lived in a very small world at the time,” Tosh told me, “in the household with my dad and mom. So I had not that much outside influences, except for TV and radio later. And then through my father’s friends.”

Tosh’s father’s friends included a roster that reads like a who’s who of classic Hollywood and the art and rock and roll worlds. In his childhood, Rolling Stones Brian Jones and Keith Richards would drop by for a visit, along with close family friends Dennis Hopper, Dean Stockwell, Russ Tamblyn and Toni Basil. Wallace had business and personal relationships with literary and art luminaries including Allen Ginsberg, Charles Bukowski, William Burroughs, Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol and others. As a young child, Tosh also hung out with the Dalai Lama, Bryan Ferry, and David Hockney at parties.

I asked Tosh: was this a Hollywood life, or something else? “I think,” he explains, “in theory, the world of the 1960s, was a smaller world, and people could connect from one bridge to another. You only need one person to sort of take you over that bridge to either side of the entertainment, movie world, or the art world.”

Tosh calls singer and choreographer Toni Basil “the great connector” in his life, and he agrees that his father Wallace also had this talent. He says it was more luck than anything else to have made so many meaningful connections.“At the time” says Tosh, “I didn’t feel anything about it, but looking back, especially writing the book, yes, I feel, blessed is I guess a good word, or I was fortunate that my family brought interesting people into my life.”

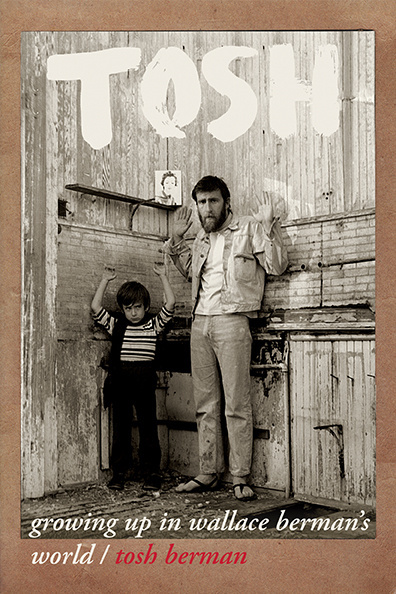

Tosh lives in Los Angeles with his wife of more than 30 years, artist and musician Lun*na Menoh. He documents his experiences growing up surrounded by this vibrant artistic community in his memoir Tosh: Growing Up In Wallace Berman’s World (City Lights Publishers, 2019). The book, which is filled with captivating memories from a man who shows the same obsessive eye for detail that was a trademark of his father’s assemblage and conceptual art, reveals his childhood and coming of age in a tale that ends with his father’s all too untimely death in a tragic car accident.

Tosh’s narrative is tightly subjective, describing in detail the progression from an awkward, sensitive child who paid close attention to the exact textures of his kindergarten friends’ clothes and the sound of their voices, to the surreal blurring of lines between life and art. In particular, Tosh’s friend Billy Gray played Bud on Father Knows Best in the late 60s. “So when I watched that show,” Tosh explains, “I would watch Billy, playing Bud, and to me there was no difference between Bud and Billy, in the character. He was always a kid, in real life. It totally blurred the lines. When I watched Father Knows Best it was like a normal American landscape.”

Yet Tosh calls his home life growing up, a flipped version of that show, where his father stayed at home and his mother worked outside, in sales. As he was too bright for the dull lessons of grade school, a large part of Tosh’s education happened watching his father create art in the studio, creating assemblage art for galleries and record covers, and later as he moved into sculptures. “I didn’t have any really close childhood friends at the time, so my dad, he took care of me,” Tosh says. “It doesn’t mean like he looked after me every second. Basically I just had to be there while he was working.”

Wallace Berman’s eccentric works incorporated diverse elements, including mimeographed images in stark black and white, along with increasing use of Hebrew letters, particularly in the conceptual sculptures of his later works. “It’s interesting,” he says. “The Kabbalah was basically I think through his interest in people like Marcel Duchamp, Artaud, and lot of the 19th century poets had an interest in Kabbalah.”

Tosh writes that despite his father’s unconventional ways, his parents always seemed to have enough money to get by, as their income was supplied by his mother Shirley’s work outside the home, in addition to his father’s artworks sales. Tosh attributes this to luck, “to this day, still luck.” Tosh spent a lot of time at his maternal grandparents’ as well. “Basically, I lived in a very small world at the time, in the household with my dad and mom. So I had not that many outside influences, except for TV and radio later. And then through my father’s friends. So I didn’t know what was normal at what was not normal.”

Tosh remembers his father’s use of music in the studio, where he would often play the same song over and over to achieve a kind of creative trance that gave him inspiration. And though Tosh says his dad had a great antenna for good music, it was his way of consuming songs that was unusual. “His obsessiveness with music is that he’ll play one record over and over and over and over again,” Tosh says. “I don’t think he ever got sick of it, it was like a meditation thing for him.” Science points to changes in the brain that music can inspire, and that looks like the case with Wallace.

After a bad experience being arrested in Los Angeles’ Ferus Gallery in 1957 for a purportedly pornographic element in a one of his collages, Wallace rejected the gallery system. It was his first exhibition, and it resulted in one or two nights in jail. Dean Stockwell posted the $150 bail. “When he got arrested for the gallery,” he said ‘I’ll never ever join a gallery. It’s something he didn’t want to do, he didn’t like the system. He didn’t dislike galleries, or the art world, but he himself was not comfortable being part of a company.”

So in 1957, Wallace Berman, as a self-taught artist who started out finishing furniture learned about art history from View, a New York publication that he collected, became a free agent, still selling his art to galleries to contribute to the economy of the Berman household, but never joining an exhibition (at least not until Tosh arranged for many shows, decades later, starting in the 2000’s.). Tosh believes that had his father played the gallery game in his lifetime, things would have been different. “I’m sure if he had a big gallery behind him,” Tosh explains, “he’d be this mega huge artist now. And museum representation everywhere. So since he did not have gallery representation, and he just basically just dealt with people who he liked or respected…it’s not even like he had a plan. He makes a piece, he sells a piece. So that means he would sell to somebody he actually knew. He might even go to that collector, directly , or he would go to a gallerist, and say ‘here’s a piece I would like to sell. I would like a certain amount of money for this, whatever you make is totally yours. You have this piece for a couple of months. If you sell it, great. It not, I want it back.’

This approach, along with the notoriety of Wallace’s hand printed publication Semina, limited to 100 copies which are now quite valuable, word of mouth, and Tosh’s mom Shirley’s income from work outside the home, kept the family afloat. “He was eccentric,” Tosh says. “he was deeply eccentric. But he had no interest in really making money off Semina. He just basically just wanted to enlarge a group of people who had a common interest.” At one point their friend Dean Stockwell bought the Berman’s a home in Topanga Canyon.

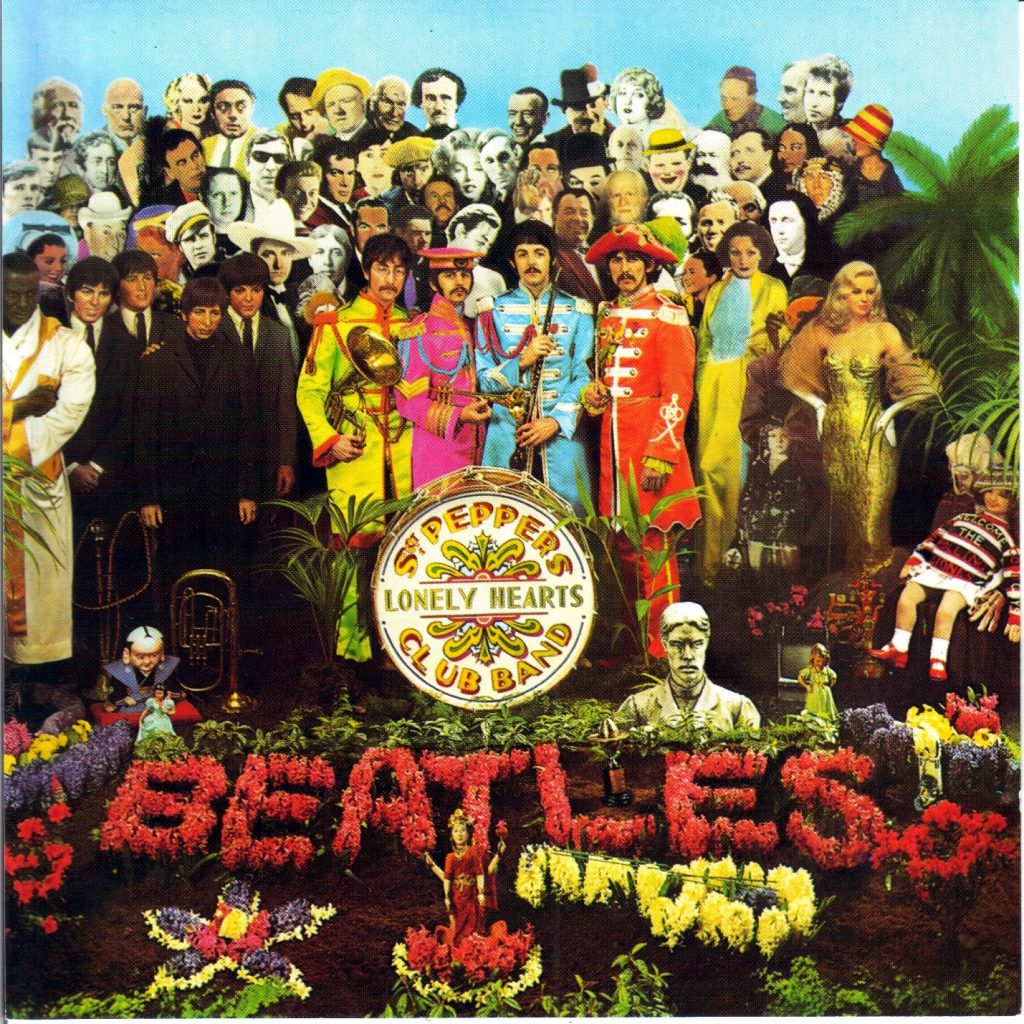

Eventually Wallace met Robert Fraser, a prominent London Art dealer. It was Fraser who helped the elder Berman to sell dozens of pieces, and who arranged for Wallace’s photo to be included in the collage on the Beatles’ 1967 album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band.” One might expect anyone to be thrilled with such exposure. But for Wallace it was different. Tosh explains: “Shrugged it off is too strong a word. He just basically did not pay that much attention to it. He never had, he never felt like ‘I’m on the Beatle’s cover, the greatest album ever made.’ I did, but he did not..”

So though Wallace was surrounded by stars of Hollywood and the art world, he remained low key about it all. “He never looked at the world in that sense. You know, like being, though a lot of celebrities were attracted to him, they like him a lot, and think basically because of his attitudes towards that world, was not like ‘you’re somebody special or not.’”

Tosh describes his father as having outstanding taste in music, with favorites often overlapping with Tosh’s or even being decades ahead. “It’s interesting,” Tosh says, “that he brought into the house this culty stuff, not big hits at all. But he picked up on things that ‘this person’s really good.’ He picked up on what’s good and what’s bad.” Tosh recalls his father bringing him in the 70s to the famous David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust concert at the Santa Monica Civic, as well as to Iggy Pop and Roxy Music shows.

Had his father Wallace not had his life cut short, at the age of 50 in a car crash caused by an intoxicated driver, Tosh thinks he would have continued his ventures into conceptual art. “He was sort of going back to more conceptual pieces,” Tosh explains. “Like he was making sculptures using rocks, real rocks. And painting Hebrew or Kabbalah writing on it. So I think he was getting away, at the time of his death, he was getting away from sort of the technology and more like into hand painting rocks and that sort of thing. When he died, he was working on these rock sculptures that he would make and leave it on the beach, and photograph them. Somewhere down the line, someone would find them. And I think he sort of liked the idea of someone finding them or not finding them.”

To this day, Tosh avoids visiting the homes around Los Angeles where he grew up. ‘It’s too depressing to me to do that,” he says “I lost my dad, but also, you know, writing this book, I’m in control of my memories, and I don’t want to be going back to someplace, and reflecting something there.”

Tosh has two new books in the works, including one that will honor his father and deal with the grieving process. “I’m working on a collection of short stories, and essays, so I’m working on making that into a manuscript right now. And for the future I’m working on memoir, about the aftermath of my father’s death. I’ll go into that in detail.”

In addition to his work as an author, Tosh is a publisher, owner of TamTam Books, publisher of works by Boris Vian and Serge Gainsbourg, as well as by Tosh himself and his wife Lun*na.

finis

“Tosh: Growing Up In Wallace Berman’s World” at City Lights Bookstore